Disaster, Loss, and Coming Home Again

BT/FA is my “home” site, even though I live in Durham now. It was Jim and Shannon who first convinced me to put on funny clothes and talk to people about spinning. It didn’t take long for me to ask my mom to make an outfit for me to wear during events. For a number of years, BT/FA was pretty much the only place I did living history. It was there that I learned how to tell the stories of the past in ways that people today could relate to. The erosion on the waterfront, and the artifacts recovered as a result, also provided a topic for my MA thesis and plenty of conference papers over the years. While I can’t quite walk the site blindfolded, I can definitely give a tour walking backwards the whole time.

On September 8, 2018, I was down at Brunswick Town/Fort Anderson State Historic Site for the Spanish Alarm program. It’s one of the smaller, more low-key living history events the site does, so it’s fun to help with. It had been a tough couple of months for me, so it was nice to do an “easy” event. At the same time that I was trying to get visitors to try out some of the games people played during the 18th century, Hurricane Florence was out in the Atlantic doing all sorts of weird things. What I didn’t realize that day was that it was going to be the about five months before I would be back at the site. And when I came back, things would have changed in ways that I couldn’t have predicted.

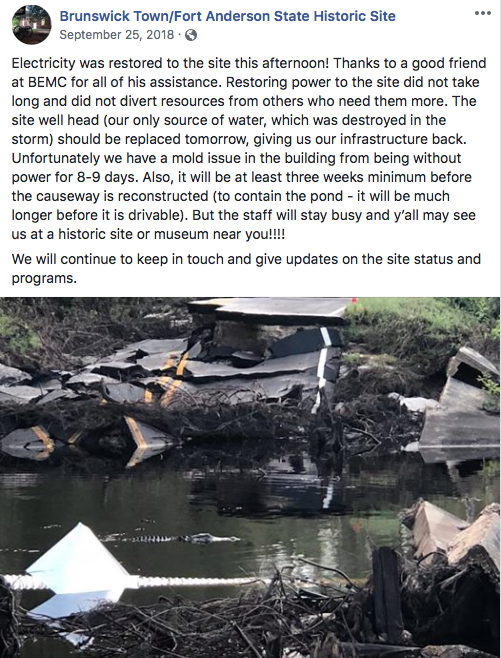

While Florence weakened significantly before making landfall, the fact that came ashore just south of Wrightsville Beach meant that BT/FA and its immediate surroundings took a massive hit. The storm also slowed down as it made its final approach, meaning that literal feet of rain fell on the area as Florence moved through. Not ideal, given that the only road to and from BT/FA is a road over the top of the causeway that forms the edge of Orton Pond. When dams burst in nearby Boiling Springs Lake, Orton Pond took on more water, washing away the causeway – and the road to the site with it. BT/FA became an island, accessible only by boat from the Cape Fear River. Lingering flooding and road issues in the region meant that site staff who had evacuated couldn’t get back home, let alone to the site.

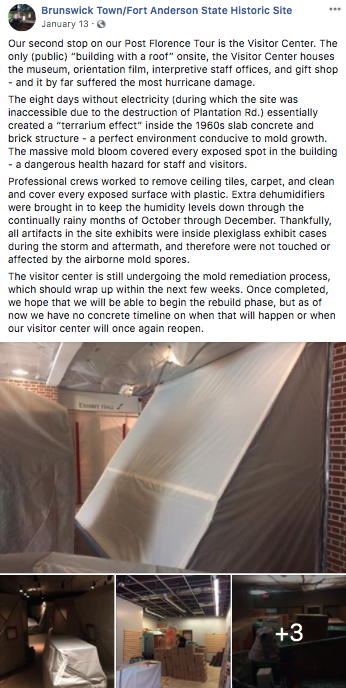

In addition to the flooding/access problem, the site lost power for 9 days. The site’s visitor center was built in the 1960s, and even with air conditioning, the humidity inside goes up a lot during the warm months. No power meant that mold started growing everywhere in the building. In the HVAC vents. In the AV room where visitors would watch the site orientation film. In the staff’s offices.

While the causeway was rebuilt a lot faster than had been expected, the site grounds weren’t able to reopen until December 4th, and telephone service wasn’t restored until January 18th, 2019. This meant that the site’s October festivities – the annual Heritage Days program and Port Brunswick Days were cancelled. During Heritage Days, all of Brunswick County’s 4th graders (around 1,000 students, along with teachers and parents) visit the site. Port Brunswick Days brings some of these students back with their families in tow, and other members of the public come to see the site alive with costumed interpreters. If you’ve been to Port Brunswick Days, you’ve seen me sitting at my spinning wheel, talking to people about how yarn is made and the clothing that women wore during the time Brunswick was a bustling port.

On February 16, 2019, I headed back to BT/FA for the Engineering a Fort event. Rather than the typical two-day February event, this was a single day event – it’s hard to plan a large two-day event when you don’t know what space you’ll have available. Mold remediation in the Visitor Center has been completed, replacement of carpeting, ceiling tiles, and some sheetrock has not been taken care of yet, so the building was not open for visitors (aside from the bathrooms – outside, off the patio area). The staff is currently working out of a trailer parked next to the visitor center, which is awfully small for three to five people to be in at the same time.

Talking to staff ahead of time and seeing pictures meant that I had something of an idea of what the site would look like when I got there. But honestly, nothing could prepare me for what I saw when I got there. Driving to the site, I saw trees that had been down since the storm, and holes where trees had been. There was standing water in many places along Plantation Road back to the site (because of course we’ve had the wettest fall and winter on record). As usual, I drove down the access road and parked by the Maintenance Building and walked over to the Visitor Center. I’m a creature of habit, and went to the front door to go in. Of course that wasn’t an option, and I saw the sign that told visitors why the building was closed. A little later I was given a tour of the building as it currently is. There’s plastic sheeting covering the front desk, the cannon and Claude Howell mosaic, and the exhibit cases. The chairs from the AV room are stacked and swathed in plastic wrap. Everything from people’s offices, as well as the gift shop, is in boxes that are stacked all over the place. They’re sort of labeled, but it’s hard to find things (we had to go looking for tape at one point before the event started). Industrial dehumidifiers stand in various places inside. It looked like someone’s house right before they move. Except in this case, no one is going anywhere. Everything is just waiting.

Towards the end of the event, I took a walk through the site. I’d waited until then because I knew that whatever I saw was going to be hard. Walking through the Fort Anderson earthworks wasn’t too bad – they’ve withstood a lot. The biggest thing I noticed was that one of the magazines that’s been slowly collapsing seems to have a larger depression in it than the last time I’d looked. But not surprising with all the rain. Once I got to the waterfront, I started to see more evidence of the storm. A large corrugated plastic tube washed up into the marsh grass near Dry’s Wharf. The quantity of debris washed up and over to the other side of the walkway. The missing trees down around the clay pit. The surprising openness around the pond due to trees that had come down there.

As I climbed the path up the bluff into the colonial town, I was confronted with more evidence of the storm. There’s a pair of Crape Myrtles right next to Judge Moore’s. There are records of Crape Myrtles having been brought to the town, and those were the only two on the site when Stan South initially cleared the area. They might be descendants of trees brought here during the 18th century. They were covered in lichen and Spanish Moss, and look like they’d taken a beating. When I came to where the walkway turns back towards the Visitor Center by Hepburn-Reynolds, I really understood how much debris had been cleared from the site. There were two large piles away from the path – one of branches and other smallish debris, and one of tree trunk sections. Disposal is a challenge because of all the other random debris mixed in with the tree bits.

Coming back to the site and seeing this damage was a punch in the gut for me. I’m there probably a dozen days out of the year, but it’s home. When I go to events there, I get to see some folks I only see at BT/FA events. I get to talk to visitors about the site’s history and archaeology. I get to say hello to artifacts that I helped recover and conserve. So I felt helpless and frustrated when I saw the damage. Six months later, and there’s so much left to do. Yes, the worst of it has been dealt with. But what’s left – the little things – are just as important. I’m in awe of the staff, coming to work every day, doing their jobs to the best of their ability, despite lacking the things they need. But having to make do takes its toll. Repairs need to be completed so that a new normal can be achieved.

As I write this (six months after Florence made landfall), there is still no news on when the Visitor Center will be open to the public again. This means that visitors can’t see the artifacts recovered by Stan South when he excavated parts of Brunswick during the 1950s and 1960s, or during the more recent William Peace University Field Schools. That they can’t see the mosaic that Claude Howell created, depicting activity on the town’s waterfront in the 18th century. That they can’t see the Fort Anderson garrison flag that was purchased from an antiques dealer, conserved, and put on display in the portion of the exhibit hall dedicated to the Civil War. That talks during events have to be done in a tent outside, where daylight makes it hard to see the PowerPoint slides a presenter is using. That there’s less space to do event-related activities when the weather is bad. And while I’ll be the first to say that the site itself is beautiful, it’s the indoor activities that often add value for visitors. Because it’s in there that they can find all the things that put what they’re seeing outside into context. And that context is critical to understanding the site’s importance to history.